An interval is the distance between two different notes, or pitches. To work out an interval, you count the top and bottom note as well as all the notes in between. For example, to work out the interval formed by C to G, where C is the bottom note: you would count CDEFG, which is 5 notes. Therefore C to G forms an interval of a 5th. For the interval formed by C to D, you would just count C and D, which means the interval is a 2nd. For C to E the interval is a 3rd. C to F is a 4th, C to A is a 6th, C to B is a 7th. C to the next C is an 8th, which we call an octave, or 8ve.

You can get different kinds of 2nds, 3rds, 4ths, 5ths, 6ths, 7ths and 8ves.

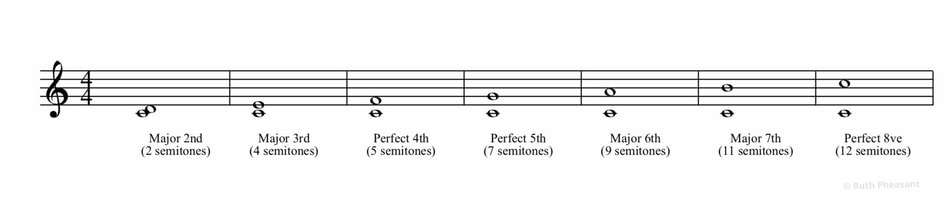

In any major scale, with the key note as the bottom note of an interval, all the intervals are called major or perfect intervals. See the picture below of a C major scale with all the intervals within it, using C as the lower note. In brackets you can see how many semitones* make up each interval.

You can get different kinds of 2nds, 3rds, 4ths, 5ths, 6ths, 7ths and 8ves.

In any major scale, with the key note as the bottom note of an interval, all the intervals are called major or perfect intervals. See the picture below of a C major scale with all the intervals within it, using C as the lower note. In brackets you can see how many semitones* make up each interval.

*A semitone is the smallest distance from one pitch to another, or the shortest distance from one key to another on the piano. See this picture showing the 7 semitones that make up a perfect fifth, from C to G on the piano. Each green arrow shows the distance of a semitone:

Any major scale will contain the same pattern of intervals shown above, when the key note is used as the bottom note of the interval.

If you change the top note of the interval so that it is no longer one of the notes within the major scale, e.g. by sharpening or flattening it, you get an interval that is not major or perfect.

For example, if you take the major 3rd - C to E, and change the E to E flat, you get a minor 3rd. So, C to E flat is a minor 3rd. By changing the E to E flat, you have made the interval a semitone smaller. (The major 3rd is 4 semitones, the minor 3rd is 3 semitones.)

Any time you make a major interval a semitone smaller, you get a minor interval. So, as another example, if you take the major 6th: C to A, and change the A to A flat, you end up with a minor 6th. So, C to A flat is a minor 6th.

If you make a perfect interval (or a minor interval) a semitone smaller, you get a diminished interval. Eg. C to G is a perfect 5th. If you change the G to G flat, you get a diminished 5th. So, C to G flat is a diminished 5th.

If you make either a major or perfect interval a semitone bigger, you get an augmented interval. Eg. C to F is a perfect 4th. If you change the F to F sharp you get an augmented 4th. So, C to F sharp is an augmented 4th.

Notice how F sharp is the same key on the piano as G flat - the two notes are enharmonic equivalents, i.e. the same pitch but with different names. So, even though the interval of C to F sharp looks exactly the same as the interval of C to G flat on the piano, we call them something different depending on which letter name they use. An augmented 4th has the same number of semitones as a diminished 5th, but the choice of letter names will determine whether we call it a 4th or 5th. C to F is always a kind of 4th no matter what kind of C or F (i.e. it doesn’t matter whether the C or F is sharpened or flattened), because you count 4 letter names - C D E F. C to G is always a kind of 5th because you count 5 letter names - C D E F G.

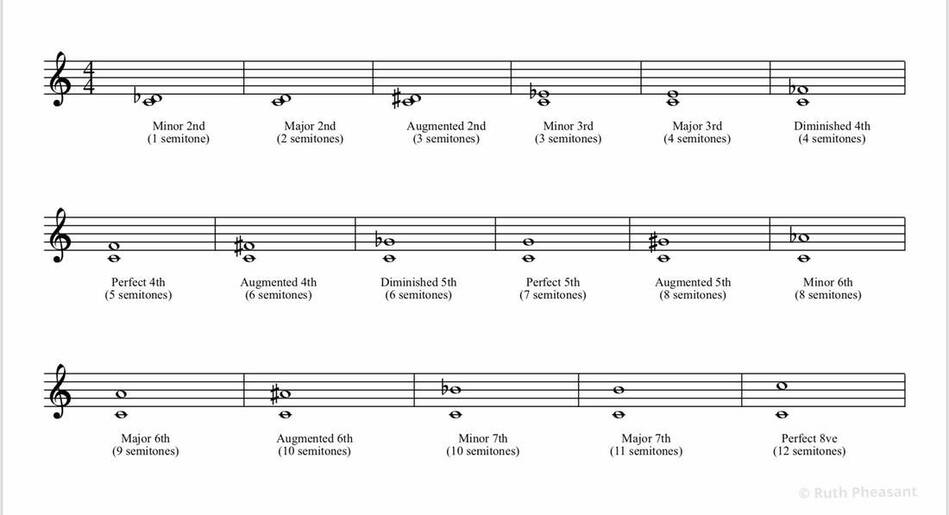

Here is a picture of more intervals using C as the lower note:

If you change the top note of the interval so that it is no longer one of the notes within the major scale, e.g. by sharpening or flattening it, you get an interval that is not major or perfect.

For example, if you take the major 3rd - C to E, and change the E to E flat, you get a minor 3rd. So, C to E flat is a minor 3rd. By changing the E to E flat, you have made the interval a semitone smaller. (The major 3rd is 4 semitones, the minor 3rd is 3 semitones.)

Any time you make a major interval a semitone smaller, you get a minor interval. So, as another example, if you take the major 6th: C to A, and change the A to A flat, you end up with a minor 6th. So, C to A flat is a minor 6th.

If you make a perfect interval (or a minor interval) a semitone smaller, you get a diminished interval. Eg. C to G is a perfect 5th. If you change the G to G flat, you get a diminished 5th. So, C to G flat is a diminished 5th.

If you make either a major or perfect interval a semitone bigger, you get an augmented interval. Eg. C to F is a perfect 4th. If you change the F to F sharp you get an augmented 4th. So, C to F sharp is an augmented 4th.

Notice how F sharp is the same key on the piano as G flat - the two notes are enharmonic equivalents, i.e. the same pitch but with different names. So, even though the interval of C to F sharp looks exactly the same as the interval of C to G flat on the piano, we call them something different depending on which letter name they use. An augmented 4th has the same number of semitones as a diminished 5th, but the choice of letter names will determine whether we call it a 4th or 5th. C to F is always a kind of 4th no matter what kind of C or F (i.e. it doesn’t matter whether the C or F is sharpened or flattened), because you count 4 letter names - C D E F. C to G is always a kind of 5th because you count 5 letter names - C D E F G.

Here is a picture of more intervals using C as the lower note:

Notice how there are more examples of enharmonic equivalents, and their interval names depend on their letter names. Eg, C to G sharp is an augmented 5th, but if you call the G sharp an A flat instead, the interval becomes a minor 6th. Both an augmented 5th and minor 6th will have the same number of semitones because their pitch names are enharmonic equivalents.